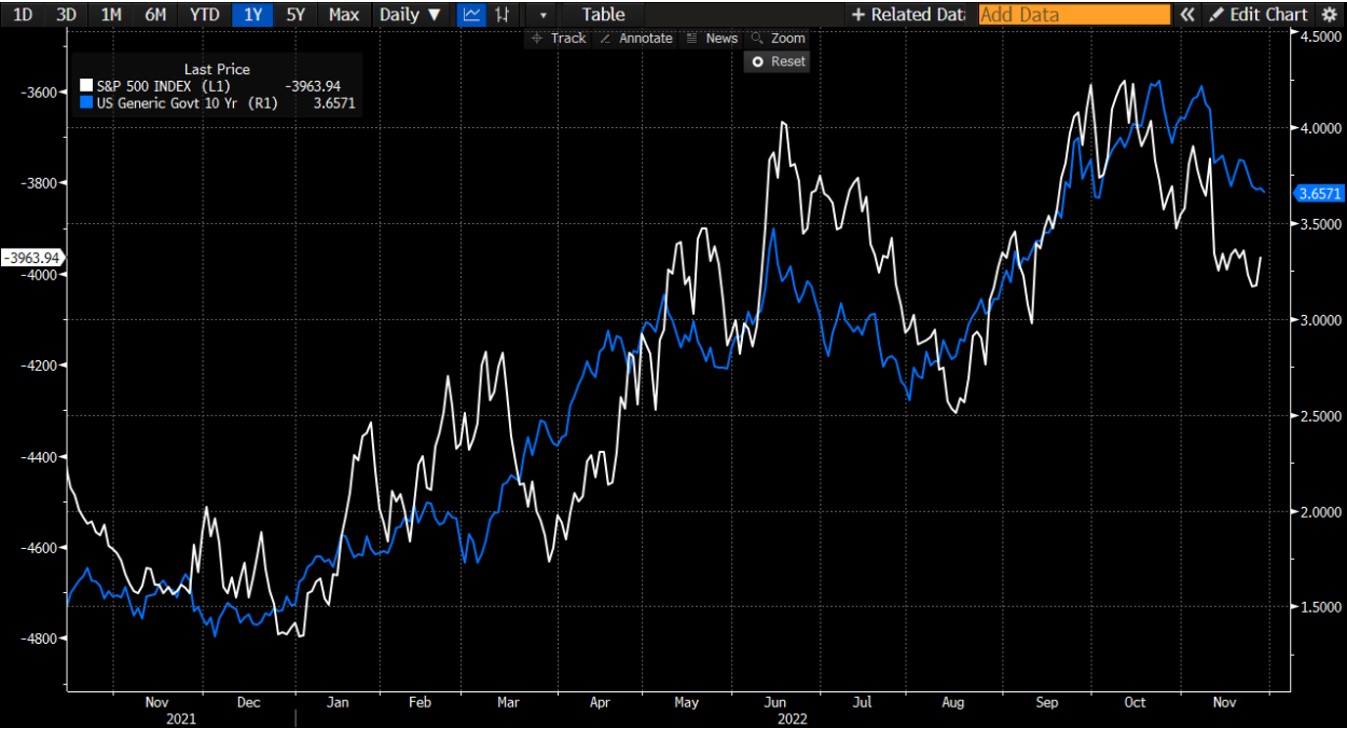

You know it if you regularly read the economic press and browse MarketScreener daily: central banks have decided to fight inflation at the risk of provoking a global recession. We will ignore the reasons for inflation, even if the exercise is similar to the fireman trying to put out the fire he started. That said, vegetation grows back faster after a good burn, so let's hope that the economy follows the same trend. Speaking of trends, I invite you to take a look at the chart below, which compares the inverse performance of the U.S. star index, the S&P 500 (in white) to that of 10-year interest rates (in blue).

From 2022 onwards, we can see that the curves tend to move together, with more or less of a lag between the peaks and troughs. Translation: when interest rates rise, the S&P 500 falls and vice versa. In this regard, it is worth noting that the rallies in August and the one underway since the beginning of October are fueled by the decline in interest rates. Hence the multi-million dollar question: how high will rates go?

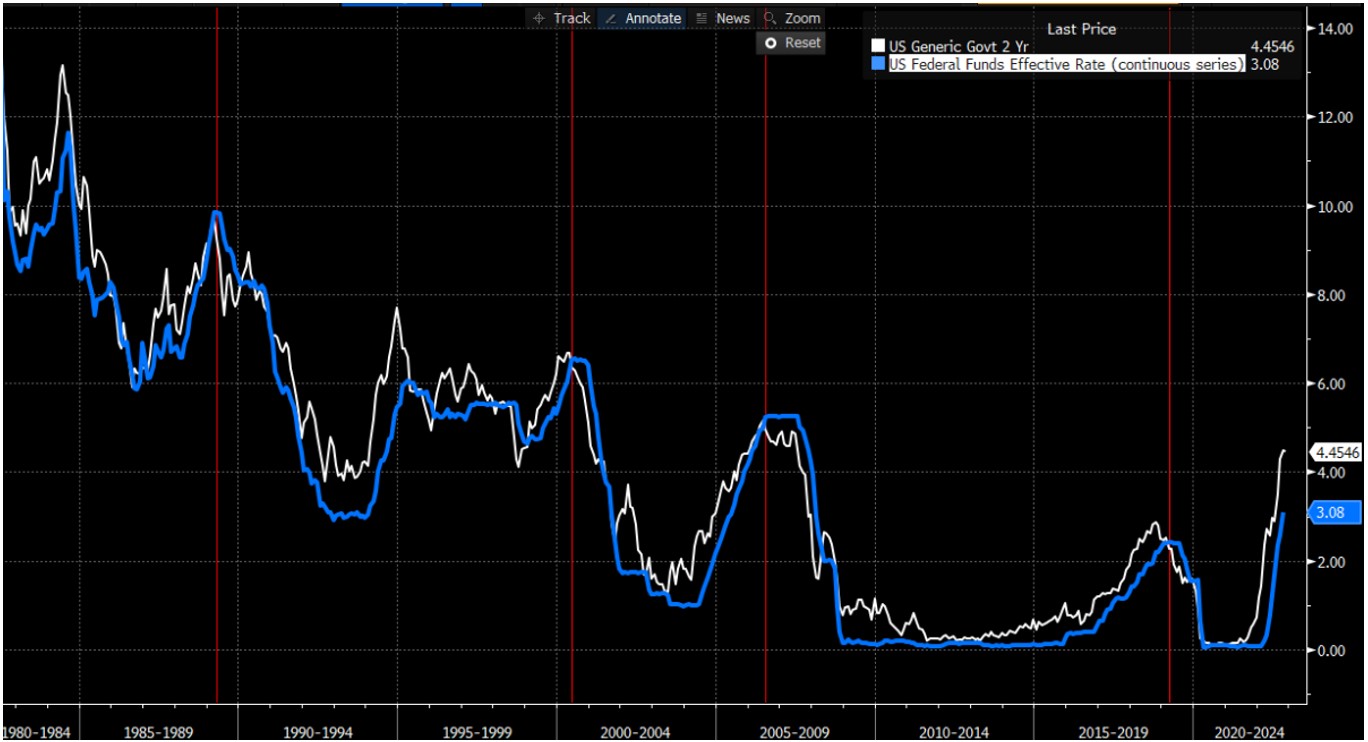

If hawks are to be believed, the (stock) market is sorely mistaken in thinking the Fed is close to a pivot. Rates must be raised substantially to effectively fight inflation. Sure, but wouldn't it be possible to determine an equilibrium point in advance? The Taylor rule, according to which the central bank must set its interest rates according to the difference between desired inflation (2%) and actual inflation (7.74% year-on-year), implies that Fed Funds should be at 5.74%. However, studies carried out at the beginning of 2000 on the Taylor rule and on half a dozen other formulas led to the following conclusion: the rule of McClellan, the inventor of many mathematical indicators that technical analysts (chartists) are familiar with, is still the one that works best, by far. In practice, it is sufficient to use the 2-year rate as a proxy for the equilibrium rate, which is currently 4.45%.

Why? Just look at the graph below. It represents the evolution of the US 2-year rate (in white) and that of the Fed Funds (in blue). Since the end of World War II, the Fed has raised rates above the equilibrium rate prior to every official recession. For monetary policy to have an effect in slowing the economy (and by extension inflation), it must go beyond what the market is already pricing in. This means that the Fed must raise rates to around 5% (4.45% + 50 basis points). And given the correlation between interest rates and the U.S. stock market, it seems unlikely that the consolidation that began last March is already over.

In a future article, we will discuss the yield curve and its impact on the health of the US stock market.

US 10Y CASH

US 10Y CASH  By

By